Samantha Yammine. Photo: Michael Barker.

![Portrait of a scientist with long dark hair [Samantha Yammine] in a lab coat next to microscopes and an open brain atlas.](http://renew.newcollege.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/SamanthaYammine.jpg)

Scroll, Swipe, Tap:

Science Goes Social

Alumna, stem cell researcher and science communicator Samantha Yammine talks brains, equity and social media.

“171 billion!” The little girl, aged maybe seven or so, shouted the number out with confident pride. She knew she had the answer right: the brain, that most complex of organs in the human body, indeed contains 171 billion cells, thousands of different types of them. She had learned this fact from a video on YouTube, recorded by the woman who was now standing in front of her, simultaneously amazed and delighted that her tireless work of disseminating science knowledge via social media was paying off exactly as intended by reaching far-flung, diverse audiences beyond the grasp of the conventional classroom. It was Samantha Yammine’s favourite moment of 2018.

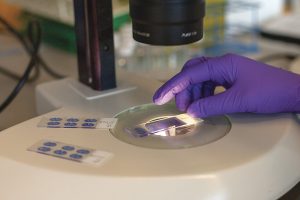

To most of her nearly 33,000 followers, Yammine (New ’12) is simply science.sam, the prolific, capable and big-hearted neuroscientist who for the past two and a half years has shared her stem cell research and all manner of scientific findings multiple times a day through visually compelling posts and stories on Instagram, her preferred platform. We find her preparing cell cultures, peering at lone neurons through a microscope, sharing notes for a radio interview on different kinds of clouds, or, for Valentine’s Day, say, answering the question “What is love?” with a decidedly unromantic statement: “Not to sound heartless, but, neuroscientifically, love can be described as a ‘motivational state’—meaning it activates some primitive parts of our brains that help reinforce goal-oriented behaviour.” So there. Go ahead and break that heart-shaped bowl your partner gave you!

Sam holding cell culture plates, much in the way she does for Instagram, to educate her followers on her work and science in general.

While some of the images Yammine shares on Instagram are truly stunning and the tone of her posts always charms with warmth, humour and a few choice emojis, her account remains focused on evidence-based science knowledge—its production, its distribution, its mobilization and, equally important, the excitement and sense of wonder it can elicit. This focus should come as no surprise from a PhD candidate in the University of Toronto’s Department of Molecular Genetics who researches how stem cells build the brain cell by cell before birth and how those same stem cells can be targeted to activate regeneration after injuries such as a stroke. Most of her colleagues applaud Yammine’s dexterous use of social platforms to provide an inside view of the scientist’s life, but some still find the tenets of science and social media diametrically opposed. While Instagram tends to promote carefully curated fluff, they argue, research in the lab requires rigour and often unappealing repetition. Besides, when studies have highlighted the detrimental effects of too much screen time, how can a scientist encourage, and engage in, even more by posting so frequently?

Twenty-eight-year-old Yammine has no illusions about some of the uglier realities of Twitter and Co. As a woman of her time, she has come into sometimes intimate contact with the flaming wars, the superficiality, the inappropriate and hateful remarks, the group think—and the non-think. Yet she also sees something else. Potential. Immense potential for the democratization of knowledge. “The biggest strength of social media I’ve seen in the two-plus years I’ve been online is the ability to form long-term relations with many people at once,” she says.

More than anything, Instagram serves Yammine as a teaching tool. She joined in 2016 on the recommendation of a friend to share with the widest audience possible her love of science, which has fuelled her since childhood. In an era of truthiness, fake news and health and wellness claims sometimes taken wildly out of context (remember, her area of expertise is stem cells), Yammine wanted to counter with the real deal: the particularities, the questions, the many unknowns. Complexity, to her, is nothing to be frightened of, just a fascinating fact of life—and the task of the expert to translate into simple terms for others.

She also specifically wanted to reach groups and individuals not typically targeted by STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education. “We all have the responsibility to democratize knowledge and share with empathy what we know,” she asserts, which is why building relationships of trust is so important. Yammine wants her followers—no matter how old they are, where they live in the world or how sophisticated their understanding of science—to feel comfortable asking anything at all about the field.

The pretty pictures on Instagram help with that, personalizing the experience and making it more relatable. It’s like an open-door policy: Yammine meets her audience where they already are, approachable and ready to talk. “I guess we start with the fun and then get into the science once I’ve hooked you with a nice image of a neuron or my shoes,” she admits, with her signature guttural laugh. What also helps is a deep commitment to equitable access. Yammine understands the influence she holds as an online personality, and the responsibility that comes with it. So she not only uses her platform to openly address thornier issues such as exclusion and discrimination in STEM but also models accessibility standards by closed-captioning her videos, providing detailed descriptions for all her images and using plain language. It’s a work in progress, one for which she relies in part on feedback from her followers. It was one of them, for example, who pointed Yammine toward the need for subtitled video clips.

Careful listening and observation, empathy and compassion, diversity, inclusion and access—these are recurring themes when Samantha Yammine talks hard-core science. Maybe not everyone would make that immediate association, but for her, after years of studying the brain and neuro-variance in great detail, nothing else makes sense: “Neuroscience teaches you compassion, both for others and for yourself.”

Science Sam’s Seven Tips for Spotting Factual Content (especially for the biomedical sciences)

- Ask how. Whatever claim you hear, ask how we know, how it was tested. If someone is unwilling to tell you how something works, don’t believe them.

- Ask for details and context. Who did they test it on—mice? Humans? Males only? Young college students? How many? Remember, in science there is no big, sweeping rule. Findings are always very specific and restricted.

- Learn about reproducibility. How many studies were done? Is the one you’re reading about the first one of its kind? If yes, great, but it means nothing (yet). Science doesn’t operate on individual studies, so make sure the claim has been tested broadly, over time, with compatible results.

- Check the source of the information. Do they have anything to gain? Are they open to questions and explaining? Did they link to the original study? Did they get a quotation from the researcher directly? (If the quote comes from another source, the journalist/writer didn’t have direct contact with the researcher, so content may be less accurate.)

- Double-check. Make sure you follow some experts online and include them in your echo chamber. Ask researchers your questions directly! Search for scientists using: #research; #scicomm; #scientist; @TheSTEMSquad; @RealScientists; #ScientistsWhoSelfie; #thisiswhatascientistlookslike.

- Improve your health-related Google searches. Add “NIH” or “NCBI” to your queries, check if information is consistent with that on government websites and/or with what the Mayo Clinic says, and use Wikipedia to learn more technical terms that might return more scholarly information in a search.

- For health and beauty myths—especially bizarre ones—check what Timothy Caulfield and Dr. Jennifer Gunter have to say, before spending money.

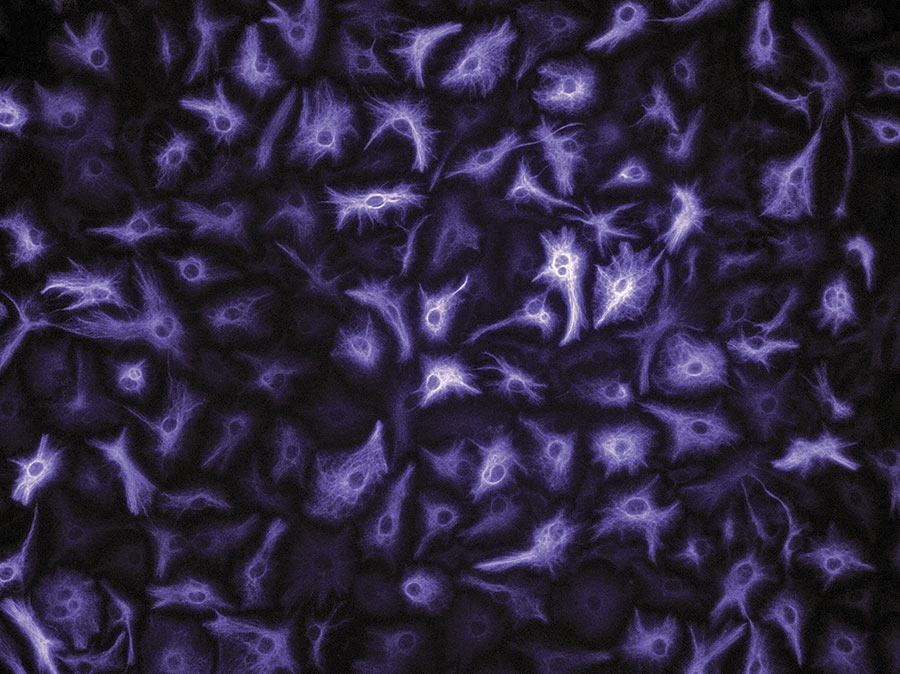

The skeletons of star-shaped cells in the brain called astrocytes, visualized here with fluorescent probes, making them purple. Astrocytes are the underdogs of the brain, even though there are billions of them. As far as scientists know now, they are important for buffering brain chemistry and supporting neurons.

![Portrait of a seated, smiling woman with box braids and folded hands [Lydia Gill in U of T’s Convocation Hall]; rows of seats visible behind her.](http://renew.newcollege.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Lydia-Gill-900px-150x150.jpg)

![Portrait of a woman with long, dark hair and glasses, smiling at the camera [Anne McGuire].](http://renew.newcollege.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/AnneMcGuire-900px-landscape-150x150.jpg)